In many digital systems, identity, authentication, and authorization are treated as if they were the same thing. In reality, they answer very different questions and play very different roles. Understanding how these concepts relate to each other is essential for making sense of how digital identity systems work and why so many of them feel confusing, restrictive, or invasive.

In everyday digital conversations, identity, authentication, and authorization are often used interchangeably. They sound similar, they usually appear together, and most systems rely on all three at the same time. But they are not the same thing. In fact, confusing these concepts is one of the main reasons why digital identity systems become overly complex, invasive, or insecure. Understanding the difference between them is a key step toward understanding how digital systems actually work.

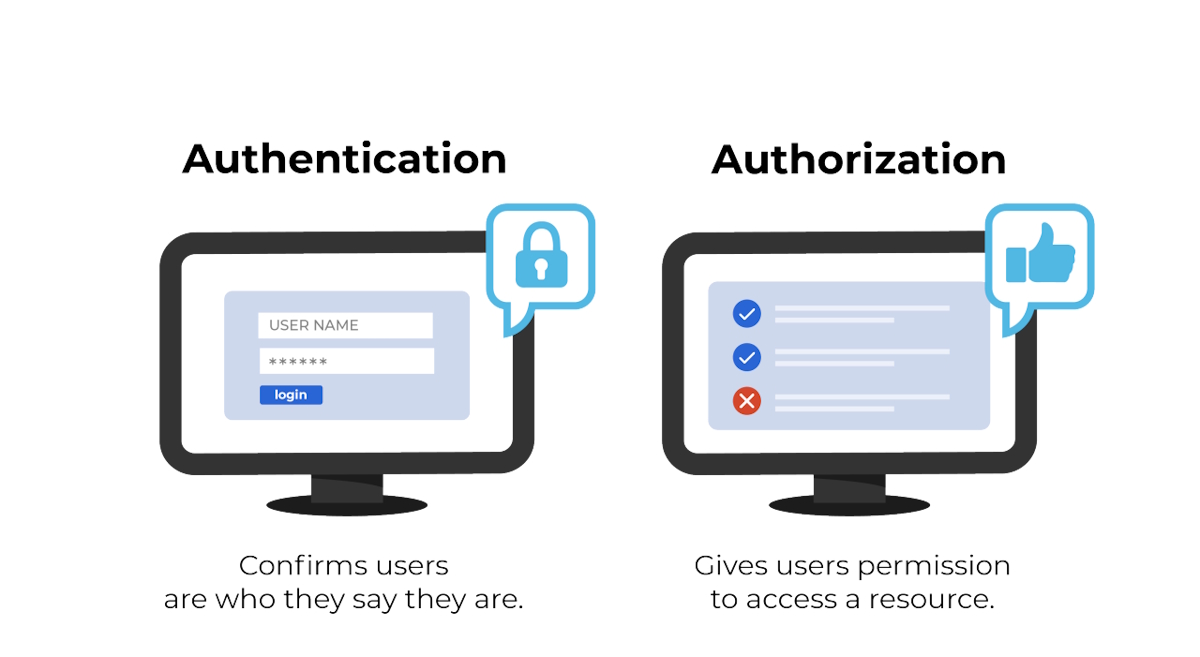

At a high level, you can think of these three concepts as answering three different questions. Identity answers who you are. Authentication answers how you prove it. Authorization answers what you are allowed to do. They are closely related, but they serve distinct roles in digital systems.

Identity: Who are you?

Identity is the concept that describes who or what an entity is. In digital systems, an identity can represent a person, an organization, a device, or even a piece of software. At its simplest, identity is a set of attributes that describe an entity: a name, an email address, an employee number, or a role.

Importantly, identity is contextual. You are not the same identity everywhere. You are a customer in a bank, an employee in a company, a user on a platform, and a private individual in your personal life. Digital systems often struggle with this reality and try to collapse identity into a single, rigid profile, which creates many of the problems we see today.

Identity by itself does not grant access or prove anything. It is simply a representation. You can claim an identity without proving it, and systems must decide whether and how to trust that claim.

Authentication: How do you prove who you are?

Authentication is the process of proving that you control or belong to a specific identity. It answers the question: how do you demonstrate that you are who you claim to be? This is where most people interact with digital identity systems on a daily basis.

Authentication typically relies on one or more of three categories: something you know (like a password or PIN), something you have (like a phone, smart card, or security key), or something you are (biometrics such as fingerprints or facial recognition). Modern systems often combine these methods to increase security.

A simple example is logging into an email account. The account itself represents an identity. Entering the correct password is the authentication step. If the password is correct, the system accepts that you are the legitimate holder of that identity. Authentication does not decide what you can do inside the system; it only confirms that you are recognized as a specific identity.

Authorization: What are you allowed to do?

Once you are authenticated, the system moves to authorization. Authorization determines what actions you are permitted to perform. It answers the question: now that we know who you are, what are you allowed to access or change?

Authorization is usually based on roles, permissions, or policies. An employee might be authorized to read internal documents but not modify them. An administrator might be authorized to manage users. A customer might be authorized to view their own data but not anyone else’s.

A practical example makes this clear. When you log into an online banking system, authentication confirms your identity. Authorization then determines whether you can view your balance, transfer money, or change account settings. Two users can be authenticated successfully but have very different authorizations depending on their roles and permissions.

Why mixing these concepts causes problems

Many digital systems blur the boundaries between identity, authentication, and authorization. Identity data is often overloaded with authentication credentials and authorization rules, all bundled into a single account. This creates rigidity and encourages excessive data collection.

For example, a system might require full identity verification just to authorize a simple action, such as proving that a user is over a certain age. Instead of separating the question “is this person over 18?” from “who exactly is this person?”, the system forces users to reveal far more identity data than necessary. This is not a technical necessity, but a design choice rooted in conceptual confusion.

How these concepts work together in practice

In a well-designed system, identity, authentication, and authorization are clearly separated but tightly coordinated. Identity defines who the entity is. Authentication verifies control over that identity. Authorization applies rules to determine permitted actions.

Imagine accessing a corporate system remotely. Your identity might be “employee of company X.” Authentication might involve a password and a security token. Authorization then checks your department, role, and clearance level to decide what systems you can access. Each step has a specific purpose, and none of them needs to know more than necessary.

Why this distinction matters for modern identity systems

As digital identity systems evolve, especially toward decentralized and privacy-preserving models, this distinction becomes even more important. New approaches aim to minimize authentication friction, reduce identity exposure, and make authorization more granular and contextual.

Understanding the difference between identity, authentication, and authorization helps explain why traditional systems feel invasive and why newer models focus on proving specific facts rather than full identities. It also clarifies how trust can be built without collecting excessive personal data.

At its core, this distinction reminds us that identity is not access, authentication is not permission, and authorization is not recognition. Treating them as separate layers is not just good architecture; it is essential for building digital systems that are secure, flexible, and respectful of the people who use them.